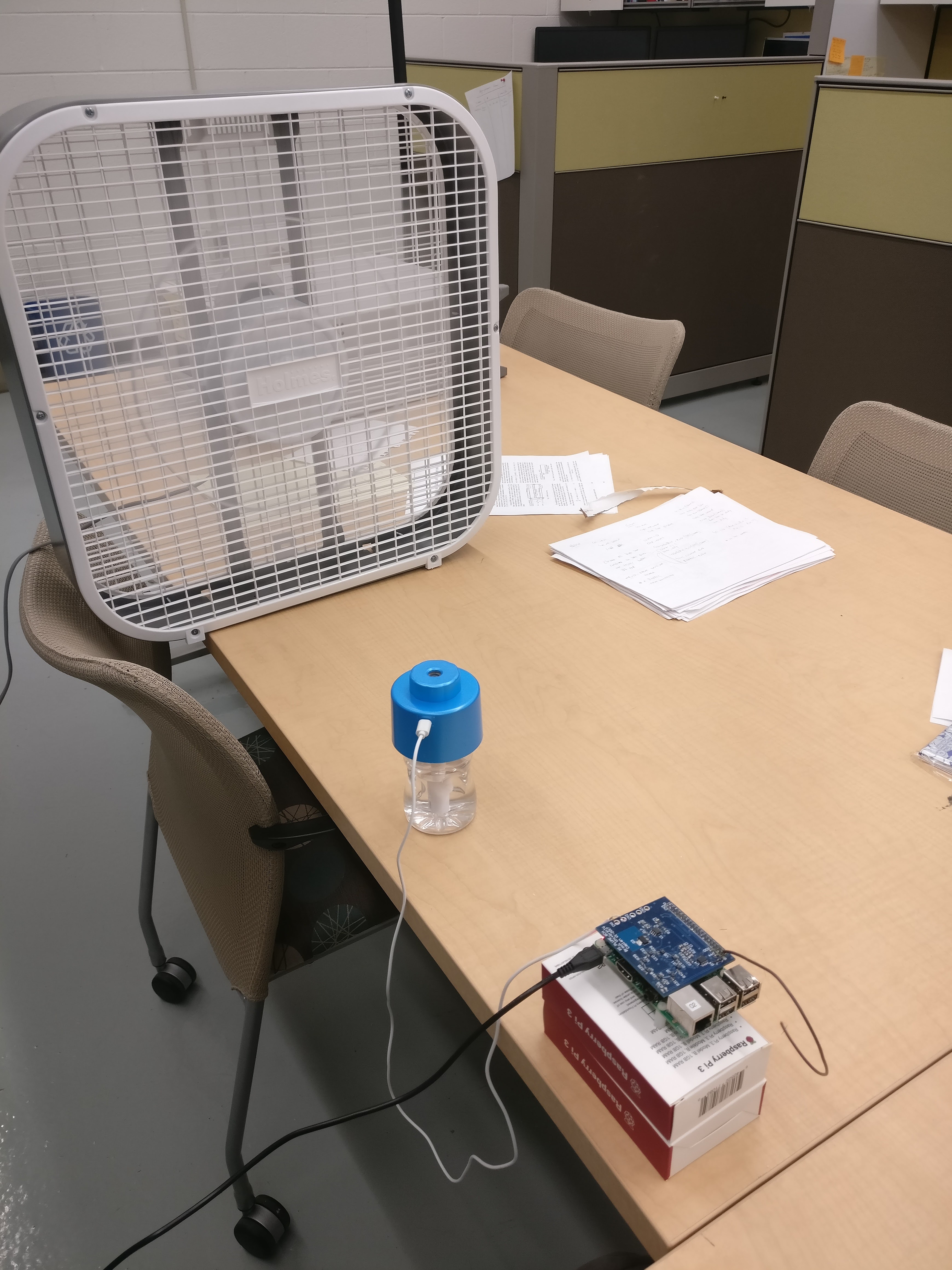

In the summer between my Sophomore and Junior years of college, I was accepted into a program called UTRA (Undergraduate Teaching and Research Awards). At Brown, this allows undergraduate placement in research labs to gain experience doing academic work. I found myself in Professor Jacob Rosenstein’s lab, working on a project to make small chemical sensing nodes on top of Raspberry Pis. This allows easy networking and data correlation from multiple locations can improve the sensitivity threshold of cheap sensors and might even allow source localization under known atmospheric conditions.

Poster and Summer Research

Over the summer, the majority of my work was spent writing Python code. Professor Rosenstein had written a quick Python script for proof-of-concept purposes, but it wasn’t scalable. I rewrote the code over the summer so that it could be applied to more sensor nodes with updated circuit boards. My work can be broken into 3 main areas: data handling, node administration, and data transfer.

Data handling

Standardizing data formats was a principal objective for my work. At the time, the lab was approaching this project from 2 different angles. First, a group of graduate students were working on expensive PID chemical sensors to test out correlation algorithms and classification techniques. Second, I was working on the distributed portion, which meant getting multiple Raspberry Pi sensor nodes networked together and running smoothly.

In order to transfer knowledge between these two approaches, a standard data format had to be designed and applied so that each trial could be analyzed by anyone in the group. We decided to use .hdf5 data format, and agreed on the data structure so that raw sensor data and chemical emission patterns could be stored. Then, I implemented this storage format using the H5PY project’s library.

Node administration

When a trial with multiple sensor nodes was run, each node had to be synchronized to start collecting and stop collecting data at the same time. In order for this to happen, the IP address of each node had to be identified on the wireless network, and then a UDP broadcast command had to be sent so that each node would collect data. A major part of my work involved changing this administration/sampling routine for better synchronization.

When I started, a UDP broadcast packet was sent each time a sample was desired to be taken. So, for a 10 second trial with 1000 samples, 100 UDP packets needed to be sent each second. In theory, each sensor node would receive these commands and send a sample back over the network. In practice, dropped samples were common over long trials. I believe this was mainly caused by buffering errors on each node.

In order to get around this, I instead sent each Pi a command at the start of the trial with the number of samples desired and the sample rate. Then, each Pi would go into a command execution loop, with timing set by the initial command. Each sample would be stored in RAM, and at the end a file was generated. This stopped the epidemic of dropped samples, and improved the reliability of each node.

Data transfer

In the previous collection paradigm, each time a sample was desired a command was sent and a data packet was expected back with the sample. When I changed the code as described above, I had to change the way that data was transferred. Because I was saving a full trial’s worth of samples in a file, it made sense to simply collect the file from each node at the end of the collection routine.

In order to do this, used a SSH client written for Python called Paramiko. This allowed me to open SSH and SFTP connections in Python so that I could collect the files from each node and save them to a central computer. This worked very well.

Later

Towards the end of the Summer, my work in Python finished and I switched to designing new circuit boards. Previously the sensor nodes consisted of a Raspberry Pi connected to a third-party DAC and ADC chip connected to a custom circuit board to house the analog VOC sensors. This was bulky and inefficient.

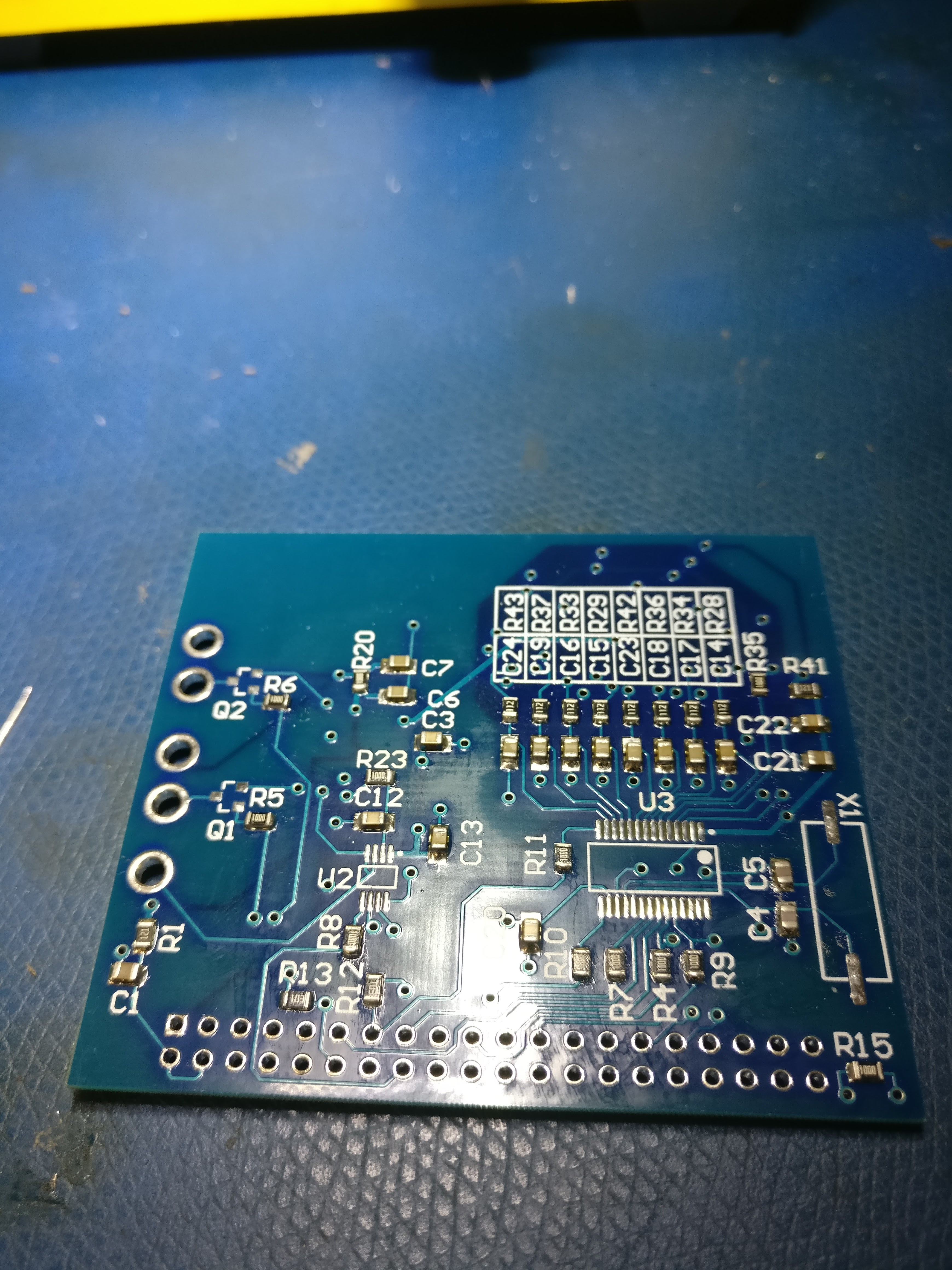

In order to design new circuit boards for more advanced trials, we decided to integrate a DAC and ADC into our own custom board, and double the amount of analog sensors on board from 4 to 8. In order to do this, I borrowed the design of the third-party DAC/ADC chip we were using, and drew up schematics for the custom board using Altium Circuitmaker. After many rounds of back and forth with Professor Rosenstein, we arrived at a final design. This was an incredibly eye opening experience in PCB bring up, and it was something that I had never accomplished previously. Because the circuit board was a mix of analog and digital systems, I learned many hands on methods to ensure circuit integrity. I also learned how to design traces by hand on a 4 layer board, incorporating analog and digital ground planes.

I decided to continue to work in the lab during the fall of my Junior year, and this time was spent assembling and testing the new circuit boards. Because the code I had written previously anticipated the increase in sensors per board, modifying the code was trivial.

The assembly and testing process was much more difficult than I expected, and I learned a lot about working with surface mount components. We decided not to use a reflow oven, so I spent a lot of time soldering all of the surface mount components using a hot air rework station and solder paste.

The testing process was especially arduous. I spent almost a week troubleshooting bad sensor readings, only to finally discover that one of my traces from the DAC was shorting out the board, and that a voltage divider had not been designed with the correct values. The first problem was easily solvable by cutting the trace with a utility knife. The second problem was solved by desoldering and resoldering new resistors with the correct values. When the boards finally worked, I was incredibly proud.

Results

Recently, the lab group published a paper that was accepted at BIOCAS 2018. One of the members forked my hardware design and added pressure sensors. Then, he built that configuration into a version of the ‘electronic nose’ concept that performed well on clustering tasks over a variety of airborne analytes. A link to the paper can be found here.